|

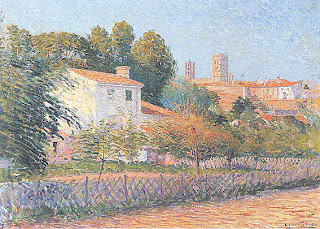

| The view from St Vincent plage. |

With

the weather in a downward spiral (at least until we leave, according to Meteo

France) and hints of the Tramontane forecast, there’s a sense of relief that we

managed at least two days on St Vincent beach.

It’s

just gone nine in the morning. There’s thunder overhead and rain is making runs

past in little surges. Everything else is blissfully peaceful.

Sitting

at the dining room table, with a steady flow of coffee, the long, narrow window

lets in the light and the cool air and the sound of the weather.

The

view beyond the tiny, wrought iron balcony encompasses a deep apricot painted

gable end with blue shuttered windows and terracotta-tiled roof. Beyond,

there’s a glimpse of the lower foothills of the Pyrenees as they slope down to

the sea.

Stand

on the balcony and there is the moulin and Fort Elme to the left; to the right,

as the hills rise away over the rooftops, the fortifications built to bombard

the Elme are visible, and then the Tour de la Madeloc.

Erected

in 1285 by James II of Majorca, to guard his Roussillon territories against

attacks from the north by the French and from the south by the Aragonese, it

was tarted up by Vauban in the 17th century.

At

656m, it can seem to follow you around. A very good place in which to build

such a tower, in other words – although it must have been a nightmare getting

the men and materials up there.

But

before the weather cooled, we spent two days on St Vincent plage, staring at

just that view, but from across the bay.

It

has almost become one of our habits when sitting there to see if either of us

can spot Le Petit Train on its slow progress up the hills, through the

vineyards and up to Fort Elme, before it disappears from view for the descent

to Port Vendres.

Made

up of three yellow ‘carriages’, pulled by an ‘engine’, you see such tourist

vehicles all over the place. But this is the one we’ve been on – and this is

the one we sit and try to spot and we catch the rays.

And

there is also, of course, Au Casot at the back of the beach. A ‘casot’, I now

know, is a small, stone hut in the vineyards.

Day

one, and I ate gambas: big, meaty things, perfect with aioli on the side.

Day

two, and it was a hulking slab of tuna, cooked ‘bleu’, just as I had asked. Divinely

moist and tasty, with a drizzle of syrupy Banyuls vinegar as a perfect compliment: a real treat.

Their ice cream is always perfection too. There is nothing complicated about what you eat at Au Casot, but the cooking is perfection and it never disappoints.

And this year, they have a new little poster on one piece of wall, making it plain that they simply do NOT do mussels.

In

between times, I bathed. More to the point, I stuck the goggles on and the

snorkel in, and popped my head below the water to look at an utterly different

world.

Fish

swam around my legs. Now usually, they swim away when you’re near them. But by

using a foot to rummage around in the pebbles and sand on the bottom, I could

keep their attention – obviously they were wondering if there was any food in

the offing.

It

was fascinating. The water is so clear you can see them in such detail: the

astonishing construction of their almost clear fins (and how they use them) and

the colours of their lithe bodies shimmering as the sunlight pierces the water.

There

were elongated fish with a single go-faster stripe; others, the shape of

gurnards (that’s not what they were), nosing into rocks and disturbing the sea

bed to find food; and baby versions of these too.

Shoals

of something that looked like small bass, shoals of small fish with delicate

yellow mouths; and others that looked like small dorade – or not so small, in

some cases, and the more the size of your dinner plate.

Shoals

of something that looked like small bass, shoals of small fish with delicate

yellow mouths; and others that looked like small dorade – or not so small, in

some cases, and the more the size of your dinner plate.

It

was charming and delightful – and not without a certain awe.

I

really must learn to swim better, so that I can do more of this.

And

then I’d sit again, drying in the sun, and watching to see if I could spot Le

Petit Train once more, and casting an eye over the pebbled beach that holds such fascinating wonders itself – like this dead dragonfly; just look at the delicacy of the wings.